POST INDEPENDENT ERA

The era after India’s independence from colonial rule starts with its partition into two halves – India and Pakistan. Lord Mountbatten became the first Governor General of free India and M.A. Jinnah that of Pakistan. The transition was violent, with blood curling massacres all over the country, ample proof to the historic acrimony that the Indians shared within themselves.

This bitterness continues till today with India and Pakistan having fought three wars since independence. Events since independence have not quite been stable for both the countries. With both of them marred by sectarian clashes and violent terrorist attacks, which by now has claimed the lives of more than a million people throughout the sub-continent. India on its part has been successful in establishing a vibrant democracy and has ever looked forward towards positive directions. But Pakistan is still struggling to establish itself as a state and has not been able to overcome the colonial hang over. With its history marred by failed democratic experiments and successful military takeovers. People of Pakistan are struck with a Herculean task of choosing between democratic farce and autocratic misrule. It is not just Pakistan that has corrupt politicians and ambitious military. India too has its share of problems with politicians and bureaucracy but the best thing in India is that people out there know their limitations. With 1 billion people having successfully tasted democracy for the past fifty years, they have successfully reaffirmed their faith time and again in the institution. At the doorsteps of the 20th century both of them provide a contrasting picture. Both of them have their fare share of problems, but on one side India is looking forward to solving them on other side Pakistan is getting messed up with it.

ASSASSINATION OF GANDHI

Rejoicing in August 1947, the man who had been in the forefront of the freedom struggle since 1919, the man who had given the message of non-violence and love and courage to the Indian people, the man who had represented the best in Indian culture and politics, was touring the hate-torn lands of Bengal and Bihar, trying to douse the communal fire and bring comfort to people who were paying through senseless slaughter the price of freedom. In reply to a message of birthday congratulations in 1947, Gandhiji said that he no longer wished to live long and that he would invoke the aid of the all-embracing Power to take me away from this ‘vale of tears’ rather than make me a helpless witness of the butchery by man become savage, whether he dares to call himself a Muslim or a Hindu or what not.

The celebrations of independence had hardly died down when on 30th January 1948; a radical minded Hindu, Nathuram Godse, assassinated Gandhiji at Birla house, just before his evening prayers. The whole nation was shocked and stricken with grief and communal violence retreated from the minds of men and women. Expressing the nation’s sorrow, Nehru spoke over the All India Radio: ‘Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere . . . The light has gone out, I said, and yet I was wrong. For the light that shone in this country was no ordinary light . . . that light represented something more than the immediate present; it represented the living, the eternal truths, reminding us of the right path, drawing us from error, taking this ancient country to freedom’.

REHABILITATION OF REFUGEES

The government had to stretch itself to the maximum to give relief to and resettle and rehabilitate the nearly six million refugees from Pakistan who had lost their all there and whose world had been turned upside down. The task took some time but it was accomplished. By 1951, the problem of the rehabilitation of the refugees from West Pakistan had been fully tackled. The task of rehabilitating and resettling refugees from East Bengal was made more difficult by the fact that the exodus of Hindus from East Bengal continued for years. While nearly all the Hindus and Sikhs from West Pakistan had migrated in one go in 1947, a large number of Hindus in East Bengal had stayed on there in the initial years of 1947 and 1948. However, as violence against Hindus broke out periodically in East Bengal, there was a steady stream of refugees from there year after year until 1971. Providing them with work and shelter and psychological assurance, therefore became a continuous and hence a difficult task. Unlike in Bengal, most of the refugees from West Punjab could occupy the large lands and property left by the Muslim migrants to Pakistan from Punjab, U.P. and Rajasthan and could therefore be resettled on land. This was not the case in West Bengal. In addition, because of linguistic affinity, it was easier for Punjabi and Sindhi refugees to settle in today’s Himachal Pradesh and Haryana and western U.P., Rajasthan and Delhi. The resettlement of the refugees from East Bengal could take place only in Bengal and to a lesser extent in Assam and Tripura. As a result; a very large number of people who had been engaged in agricultural occupations before their displacement were forced to seek survival in semi-urban and urban contexts as the underclass.

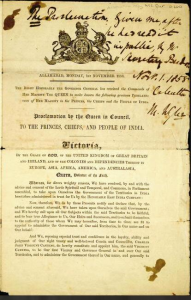

INTEGRATION OF PRINCELY STATES

Indian Independence Act, 1947 contains the following provision regarding Indian States: All treaties, agreements, etc between His Majesty`s Government and the rulers of the Indian States shall lapse. The words ‘Emperor of India’ shall be omitted from Royal Style and Titles. The Indian states will be free to accede to either of the new Dominion of India or Pakistan. Monarchy was abolished and hence, the princely states were to be annexed. In the National Provisional Government, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel headed the State Department. Patel and his chief aide, VP Menon appealed to the sense of patriotism of the Indian princes and persuaded them to join the Indian union. The annexations were to take place on the basis of surrender of three subjects of Defence, Foreign Affairs and Communication. Lord Mountbatten aided Patel in his mission too. As a result by 15th August, as many as 136 jurisdictional states acceded to the Indian union. Kashmir`s Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession on 26th October, 1947 and the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1948. V P Menon, on the other hand, successfully negotiated instruments of accession with a number of small states of Orissa with the Province of Orissa. On 18th December, the Chattisgarh rulers merged with the Central Provinces. Between the periods of 17th to 21st January 1948, Menon acquired the agreement for scores of minor states in Kathiawar to form the Union of Kathiawar, which began to govern on February 15. This set the pattern for the subsequent accession and merger of many tiny remaining states over the next five months.

For geographical and administrative reasons, Baroda and Kolhapur were annexed to the then Bomaby Province; Gujarat states were also merged with the Bombay Province. A second form of integration of 61 states was the formation of the seven centrally administered areas. Thus the states of Himachal Pradesh, Vindhya Pradesh (present day Madhya Pradesh), Tripura, Manipur, Bhopal, Kutch and Bilaspur were formed. Apart from these the states of United States of Matsya, Union of Vindhya Pradesh, Madhya Bharat, Patiala and East Punjab States Union, Rajasthan and United states of Cochin-Travancore were also integrated to the India. However, the unification of India was still incomplete without the French and Portuguese enclaves. The French authorities were more realistic when they ceded Pondicherry (Puducherry) and Chandannagore to India on 1st November, 1954.However, the Portuguese Government maintained that since Goa was part of the metropolitan territories of Portugal, it could be in no way affected by the British and French withdrawal from India. When negotiations and persuasions did not move the Portuguese government, units of Indian army had to be mobilized and Goa, Daman and Diu were liberated and annexed to India on 19th December, 1961. Thus, after much toil Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and his aides successfully integrated the Indian states to form a unified country.

THE MAKING OF THE CONSTITUTION

The Constitution of India came into force on 26 January 1950. Since then, the day is celebrated as Republic Day. However, before 1950, 26 January was called Independence Day. Since 26 January 1930, it was the day on which thousands of people, in villages, in mohallas, in towns, in small and big groups would take the independence pledge, committing themselves to the complete independence of India from British rule. It was only fitting that the new republic should come into being on that day, marking from its very inception the continuity between the struggle for independence and the adoption of the Constitution that made India a Republic. The process of the evolution of the Constitution began many decades before 26 January 1950 and has continued unabated since. Its origins lie deeply embedded in the struggle for independence from Britain and in the movements for responsible and constitutional government in the princely states. On 19 February 1946, the British government declared that they were sending a Cabinet Mission to India to resolve the whole issue of freedom and constitution making. The Cabinet Mission, which arrived in India on 24 March 1946, held prolonged discussions with Indian leaders. On 16 May 1946, having failed to secure an agreement; it announced a scheme of its own. It recognized that the best way of setting up constitution-making machinery would ‘be by election based on adult franchise; but any attempt to introduce such a step now would lead to a wholly unacceptable delay in the formulation of the new constitution. Therefore, it was decided that the newly-elected legislative assemblies of the provinces were to elect the members of the Constituent Assembly on the basis of one representative for roughly one million of the population. The Sikh and Muslim legislators were to elect their quota based on their population.

It was only after this process had been completed that the representatives of all the provinces and those of the princely states were to meet again to settle the Constitution of the Union. The Congress responded to the Cabinet Mission scheme by pointing out that in its view the Constituent Assembly, once it came into being, would be sovereign. It would have the right to accept or reject the Cabinet Mission’s proposals on specifics. The Constituent Assembly was to have 389 members. Of these, 296 were to be from British India and 93 from the princely Indian states. Initially, however, the Constituent Assembly comprised only of members from British India. Elections of these were held in July-August 1946. Of the 210 seats in the general category Congress won 199. It also won 3 out of the 4 Sikh seats from Punjab. The Congress also won 3 of the 78 Muslim seats and the 3 seats from Coorg, Ajmer Merwara, and Delhi. The total Congress tally was 208. The Muslim League won 73 out of the 78 Muslim seats. At 11 a.m., on 9 December 1946, the Constituent Assembly of India began its first session. For all practical purposes, the chronicle of independent India began on that historic day. Independence was now a matter of dates. The real responsibility of deciding the constitutional framework within which the government and people of India were to function had been transferred and assumed by the Indian people with the convening of the Constituent Assembly. Only a coup d’etat could now reverse this constitutional logic. 207 members attended the first session. The Muslim League, having failed to prevent the convening of the Assembly, now refused to join its deliberations. Consequently, the seventy-six Muslim members of the League stayed away and the four Congress Muslim members attended the session. On 11 December, Dr Rajendra Prasad was elected the permanent Chairman; an office later designated as President of the Assembly. The third session was held from 28 April to 2 May 1947 and the League still did not join. On 3 June, the Mountbatten Plan was announced which made it clear that India was to be partitioned. With India becoming independent on 15 August 1947; the Constituent Assembly became a sovereign body, and also doubled as the legislature for the new state. It was responsible for framing the Constitution as well as making ordinary laws. The work was organized into five stages: first, committees were asked to present reports on basic issues; second, B.N. Rau, the constitutional adviser, prepared an initial draft on the basis of the reports of the reports of these committees and his own research into the constitutions of other countries; third, the drafting committee, chaired by Dr Ambedkar presented a detailed draft constitution which was published for public discussion and comments; fourth, the draft constitution was discussed and amendments.

Salient features of the constitution

The Constitution of India lays down a set of rules to which the ordinary laws of the country must conform. It provides a framework for a democratic and parliamentary form of government. The Constitution also includes a list of Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles, the first, a guarantee against encroachments by the state and the second, a set of directives to the state to introduce reforms to make those rights effective. Though the decision to give India a parliamentary system was not taken without serious debate, yet the alternative of panchayat-based indirect elections and decentralized government did not have widespread support. Espoused by some Gandhians, notably Shriman Narayan, this alternative was discarded decisively in favour of a centralized parliamentary constitution.

Adult Suffrage

The Congress had demanded adult suffrage since the twenties. It was hardly likely to hesitate now that it had the opportunity to realize its dreams. A few voices advocated confining of adult suffrage to elections to the panchayats at the village level, and then indirect elections to higher-level bodies, but the overwhelming consensus was in favour of direct elections by adult suffrage not a small achievement in a Brahmanical, upper-caste dominated, male-oriented, elitist, largely illiterate, society!

Preamble

The basic philosophy of the Constitution, its moving spirit, is to be found in the Preamble. The Preamble itself was based on the Objectives Resolution drafted by Nehru and introduced in the Assembly in its first session on 13 December 1946 and adopted on 22 January 1947.The Preamble states that the people of India in the Constituent Assembly made a solemn resolve to secure to all citizens, Justice, social, economic and political; Liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship; Equality of status and of opportunity; and to promote among them all, Fraternity assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity of the nation.

Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles

The Fundamental Rights are divided into seven parts: the right of equality, the right of freedom, the right against exploitation, the right to freedom of religion, cultural and educational rights, the right to property and the right to constitutional remedies. These rights, which are incorporated in Articles 12 to 35 of the Constitution, primarily protect individuals and minority groups from arbitrary state action. But three of the articles protect the individual against the action of other private citizens: Article 17 abolishes untouchability, Article 15(2) says that no citizen shall suffer any disability in the use of shops, restaurants, wells, roads, and other public places on account of his religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth; and Article 23 prohibits forced labour, which, though it was also extracted by the colonial state and the princely states, was more commonly a characteristic of the exploitation by big, semi-feudal landlords. These rights of citizens had to be protected by the state from encroachment by other citizens. Thus, the state had to not only avoid encroaching on the citizen’s liberties; it had to ensure that other citizens did not do so either. A citizen whose fundamental right has been infringed or abridged could apply to the Supreme Court or High Court for relief and this right cannot be suspended except in case of declaration of Emergency. The courts have the right to decide whether these rights have indeed been infringed and to employ effective remedies including issuing of writs of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto and certiorari.

The Directive Principles have expressly been excluded from the purview of the courts. They are really in the nature of guidelines or instructions issued to future legislatures and executives. While the Constitution clearly intended Directive Principles and Fundamental Rights to be read together and did not envisage a conflict between the two, it is a fact that serious differences of interpretation have arisen many times on this issue.

A Secular State

The constitution declares India to be a sovereign, socialist, secular and democratic republic. Even though the terms secular (and socialist) were added only by the 42nd Amendment in 1976, the spirit embodying the Constitution was secular.

RE-ORGANISATION OF STATES

The reorganization of the states based on language, a major aspect of national consolidation and integration, came to the fore almost immediately after independence. The boundaries of provinces in pre-1947 India had been drawn in a haphazard manner as the British conquest of India had proceeded for nearly a hundred years. No heed was paid to linguistic or cultural cohesion so that most of the provinces were multi-lingual and multi-cultural. The interspersed princely states had added a further element of heterogeneity. The case for linguistic states as administrative units was very strong. Language is closely related to culture and therefore to the customs of people. Besides, the massive spread of education and growth of mass literacy can only occur through the medium of the mother tongue. Nehru appointed in August 1953 the States Reorganization Commission (SRC), with Justice Fazi Ali, K.M.Panikkar and Hridaynath Kunzru as members, to examine ‘objectively and dispassionately’ the entire question of the reorganization of the states of the union. Throughout the two years of its work, the Commission was faced with meetings, demonstrations, agitations, and hunger strikes.

Different linguistic groups clashed with each other; verbally as well as sometimes physically. The SRC submitted its report in October 1955. While laying down that due consideration should be given to administrative and economic factors, it recognized for the most part the linguistic principle and recommended redrawing of state boundaries on that basis. The Commission, however, opposed the splitting of Bombay and Punjab. Despite strong reaction to the report in many parts of the country, the SRC’s recommendations were accepted, though with certain modifications, and were quickly implemented. The States Reorganization Act was passed by parliament in November 1956. It provided for fourteen states and six centrally administered territories. The Telengana area of Hyderabad state was transferred to Andhra; merging the Malabar district of the old Madras Presidency with Travancore-Cochin created Kerala. Certain Kannada speaking areas of the states of Bombay, Madras, Hyderabad and Coorg were added to the Mysore state. Merging the states of Kutch and Saurashtra and the Marathi speaking areas of Hyderabad with it enlarged Bombay state.

The strongest reaction against the SRC’s report and the States Reorganization Act came from Maharashtra where widespread rioting broke out and eighty people were killed in Bombay city in police firings in January 1956.The opposition parties supported by a wide spectrum of public opinion students, farmers, workers, artists, and businesspersons organized a powerful protest movement. Under pressure, the government decided in June 1956 to divide the Bombay state into two linguistic states of Maharashtra and Gujarat with Bombay city forming a separate, centrally administered state. This move too was strongly opposed by the Maharashtrians. Nehru now vacillated and, unhappy at having hurt the feelings of the people of Maharashtra, reverted in July to the formation of bilingual, greater Bombay. This move was, however, opposed by the people both of Maharashtra and Gujarat. The broad-based Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti and Maha Gujarat Janata Parishad led the movements in the two parts of the state. In Maharashtra, even a large section of Congressmen joined the demand for a unilingual Maharashtra with Bombay as its capital; and C.D. Deshmukh, the Finance Minister in the Central Cabinet, resigned from his office on this question. The Gujaratis felt that they would be a minority in the new state. They too would not agree to give up Bombay city to Maharashtra. Violence and arson now spread to Ahmedabad and other parts of Gujarat. Sixteen persons were killed and 200 injured in police firings. In view of the disagreement over Bombay city, the government stuck to its decision and passed the States Reorganization Act in November 1956. However, the matter could not rest there. In the 1957 elections the Bombay Congress scraped through with a slender majority. Popular agitation continued for nearly five years. As Congress president, Indira Gandhi reopened the question and was supported by the President, S. Radhakrishnan. The government finally agreed in May 1960 to bifurcate the state of Bombay into Maharashtra and Gujarat, with Bombay city being included in Maharashtra, and Ahmedabad being made the capital of Gujarat.

The other state where an exception was made to the linguistic principle was Punjab. In 1956, the states of PEPSU had been merged with Punjab, which, however, remained a trilingual state having three language speakers ‘Punjabi, Hindi and Pahari’ within its borders. In the Punjabi-speaking part of the state, there was a strong demand for carving out a separate Punjabi Suba (Punjabi-speaking state). Unfortunately, the issue assumed communal overtones. The Sikhs, led by the Akali Dal, and the Hindus, led by the Jan Sangh, used the linguistic issue to promote communal politics. While the Hindu communalists opposed the demand for a Punjabi Suba by denying that Punjabi was their mother tongue, the Sikh communalists put forward the demand as a Sikh demand for a Sikh state, claiming Punjabi written in Gurmukhi as a Sikh language. Finally, in 1966, Indira Gandhi agreed to the division of Punjab into two Punjabi- and Hindi-speaking states of Punjab and Haryana, with the Pahari-speaking district of Kangra and a part of the Hoshiarpur district being merged with Himachal Pradesh. Chandigarh, the newly built city and capital of united Punjab, was made a Union Territory and was to serve as the joint capital of Punjab and Haryana. Thus, after more than ten years of continuous strife and popular struggles linguistic reorganization of India was largely completed, making room for greater political participation by the people.

he women.These movements came to be called socio-religious movement because the reformers felt that no change is possible in a society without reforming the religion.

he women.These movements came to be called socio-religious movement because the reformers felt that no change is possible in a society without reforming the religion.